Notes on Teaching Game Workshops by Reluctant Game Makers

Projects start as derives and have messy beginnings. They can emerge from various forms of engagement both inside and outside the public institution. A project’s start cannot be easily explained within the binaries of curatorial or artistic practice, as projects often start in a dialogical situation that also traverses different disciplines and diverse expertise and knowledge.

Marion von Osten, In the Making: In the Desert of Modernity: Colonial Planning and After

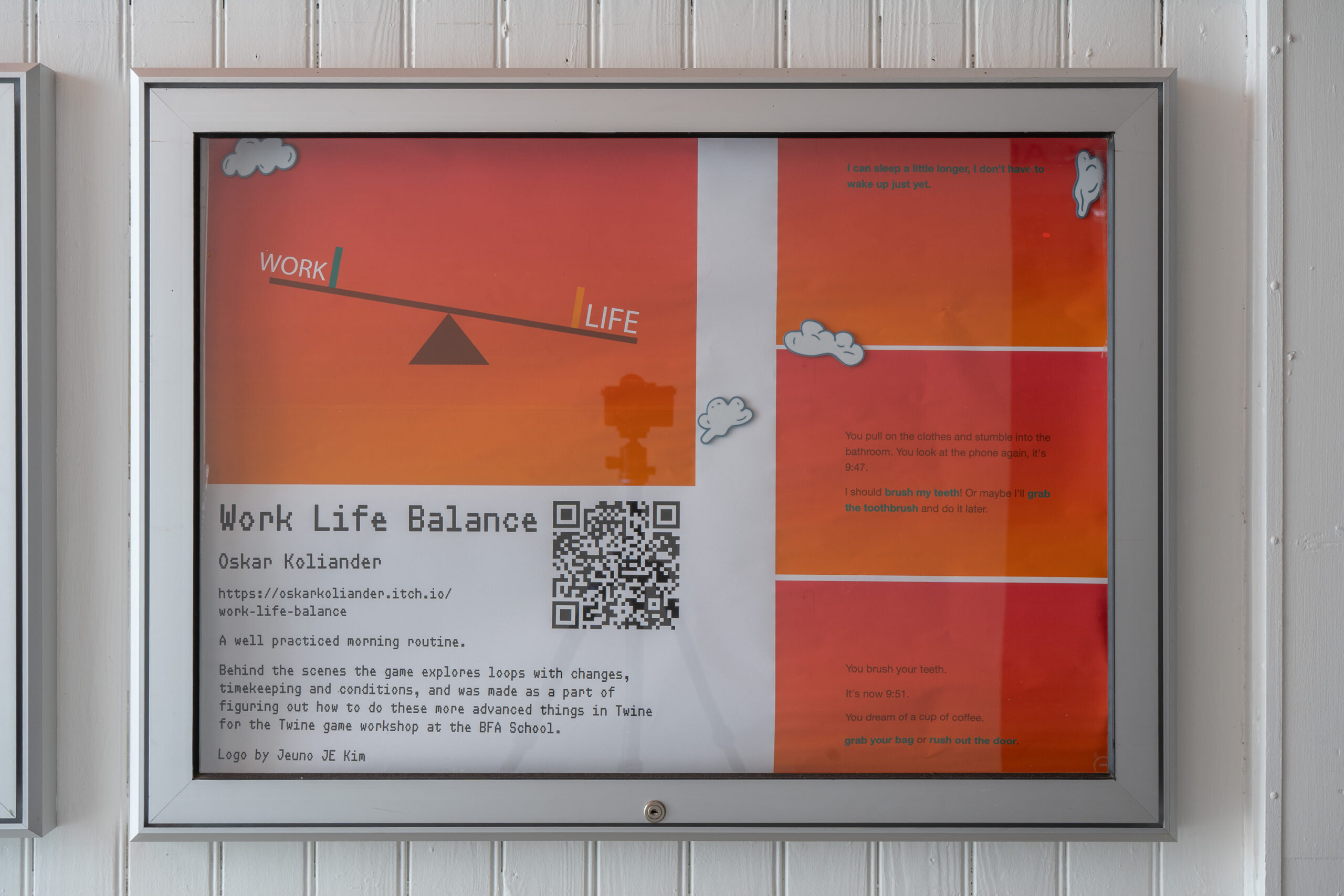

The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen is the institutional starting point for this project. Apart from employing two members of the research team – Jeuno Kim, the study leader of the BFA school, and Oskar Koliander, head of the 3D Lab – the Art Academy is also facilitating the project’s funding of the project and administrative processes. The campus is in central Copenhagen. It is a physical building that houses our various teaching activities, supplies the project with students, teachers, electricity, sour coffee and, most importantly, an institutional and communal understanding that art is both thought and practiced here.

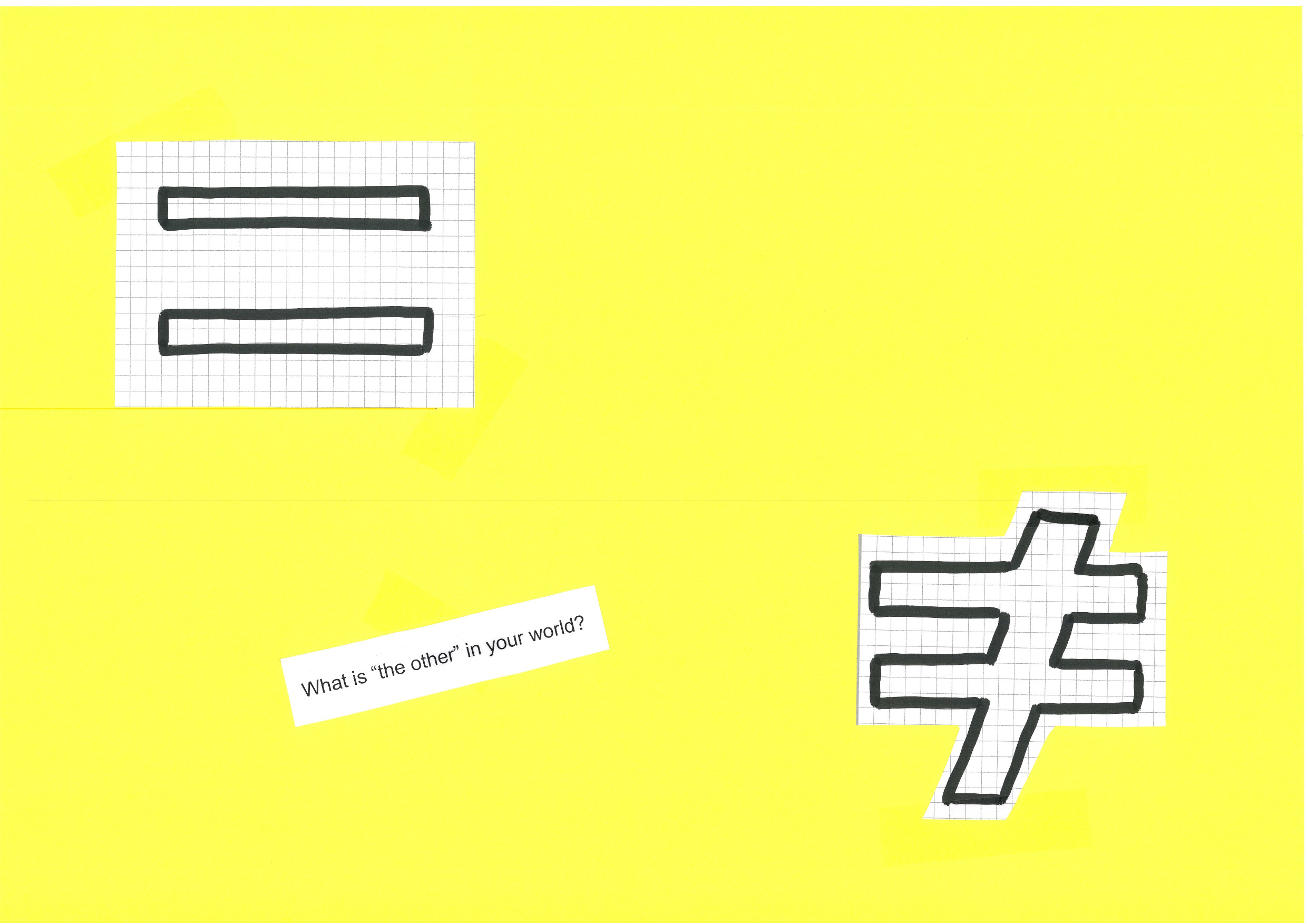

The Krabstadt Education Center (KEC) is the other reference point. KEC is a fictional school that is located in and makes use of the animated world of Krabstadt, a place where all the Nordic countries have sent their unwanted people and problems. Krabstadt as an animated world was created by artists Ewa Einhorn and Jeuno JE Kim, and during its long development as a transmedia project, its Education Center was established in collaboration with artist Karolin Meunier. This coincided with an influx of unemployed artists with PhDs that flocked to Krabstadt, prompting its municipality to create an integration program for this demographic. KEC is a school that exists between the digital and the physical, appearing as an online platform, workshops, an open house, a performance, and as a summer school in physical spaces.

Oscillating between the two academies located in Copenhagen and Krabstadt, Let’s Play has a research trajectory that flickers between games, arts education, curriculum building and playing around. Once the project has run its course at the art academy in Copenhagen, it will continue to exist, both as an archive and as a practice, in the Eggshell-White Room, which is located on the fourth floor of KEC’s main campus.

Karolin: In which ways do you think of KEC as a game?

Ewa & Jeuno: KEC has many game-like aspects. It can enter any existing teaching institution or self-organized school to create an environment that allows for playing with elements of education. KEC has several core teaching methods, one of which we call ‘situation-tailored scores.’ In its courses, participants act relatively free within a defined framework, allowing them to play around with the given parameters, rules, and suggestions. This is different from a task or an exercise because these scores are open-ended, often functioning as a starting point, for example, for a series of drawings, a game, or a text. The scores function as prompts towards something that may or may not lead to a specific outcome or result.

KEC seeks to mix the fantastical and the fictional with political and social issues. This enables participants to safely explore different questions in relation to the world they inhabit and decide how to interpret the provided frameworks. The flexibility of gameplay and its outcomes create a safe space to try things out, since, after all, it’s just a game.

K: Yes, I remember when we guest-edited an issue of the PARSE Journal as the Krabstadt Education Center. Its fictional structure not only provided a framework for the participating artists and scholars, but connecting to this world prompted them to take a playful approach to their own practices. Could you say a bit more about how the work at KEC allows us to explore issues of everyday life, such as our educational environments?

E & J: The Krabstadt narrative already brings a certain flavor to the situation. We often use scores that address the mundane, boring or frustrating aspects of education. KEC provides a specific framework for interpreting these scores, and usually there is another kind of attention available. One recurring question is: How to engage creatively with frustrating situations in our lives we normally want to push aside when we go to school? There are things we are supposed to leave out in order to learn something that we fantasize or wish will relieve us of these annoying parts of our lives – there is the promise of education as a path to a better life. But what happens when we bring those unsavory feelings into educational settings and use them to learn about how games are made?

One concrete example is inspired by a comic called “Games Adults Play” by Josh Gondelman and Molly Roth. We developed it into a score in which we asked participants to describe something frustrating in their everyday life, and to think of it as a game and to make it even more annoying. Or, in gaming terms, to think in progression and to add a level. From this perspective, fiction and play are not about escaping from reality but rather using games and fiction to explore different aspects of reality by processing it through the lens of game elements. It’s one way of exploiting the expectations that games and play can open up to look at our everyday situations and problems. By applying these specific artistic forms to a familiar context, participants can explore them in relation to their lived experiences. This also makes the concepts of games themselves more accessible and less abstract, less detached from life.

Karolin: We have often discussed KEC in relation to fiction. Even in moments when it manifests physically, for example in the form of a workshop with students, there are fictional aspects that one has to relate to, since the world of Krabstadt provides the underlying framework. So, we have considered the role of fiction and how it enables us to approach learning spaces and teaching situations. It’s interesting to now shift the focus to KEC’s gaming aspects. How does KEC engage with and provoke game-based thinking? What role do you think gaming could play in an artistic and educational context?

Jeuno & Ewa : Game-based thinking is an interesting concept often associated with game based learning. In KEC we originally derived it from Design Thinking, a problem-solving process designers use. For us, the definition of game-based thinking can be quite elastic. It begins with simple questions: What can a game be? What happens to this object, situation, or process when we call it a game? Of course, people making games have been asking these questions for decades. However, defining what a game is also circumvents the discussion on who can be part of the conversation about games in the first place, and this is where art and education come in. We are interested in cases where artists start working with games or teaching them in art schools or other artistic contexts, since artistic thinking and teaching offer a long-standing practice of questioning, breaking and pushing genre boundaries. There is an understanding that things don’t need to be what we think they are. We think that these questions of definition, form, and participation meet a different kind of resistance in an artistic context than for example in the education of game design. How can the participatory aspects of play, or the communicative tools of games have an actual bearing on the art being made? With more artists using game engines to explore ideas there is potential for what artists and educators can do with games.

Using fiction allows us to exaggerate some of the systems and challenges one finds in real schools. Game-based thinking allows us to look at a ‘problem’, generate ideas on how to address it, and come up with prototypes or ways of addressing it as a game. For example, in our own work with the game format, we looked at how admissions processes are conducted in schools where a high volume of applications has to be combed through within a set amount of time. It’s a classic game structure where time-limited situations lead to challenges and decisions that need to be made quickly. The selection process in the admissions panel becomes heated due to this pressure, with committee members battling it out, each arguing for their candidate, trying to defeat the others. Taking this situation as a starting point, we made the KEC Admissions Game, which is accessible on the PARSE Journal website. It’s a desktop game based on the mechanics of shooter games: ‘applicant’ blocks descend down, and the gameplay is to shoot down obstacles that are in the way of ‘selecting’ the applicants that are to be admitted. The selection of the admitted applicant has a direct visual outcome, where one can see how the school building is affected by applicants that are chosen to be admitted. The final outcome of the game is the design of the school building that is determined by the cohort of accepted applicants.

Karolin: The KEC Admissions Game reveals something about the real admissions process, where selections can happen quickly and intuitively. As you say, using the mechanics of a shooter game is farcical, but it also functions as a critique of certain mechanisms that are at play where the person who acts fastest gets their favorite applicant in. The question of speed and time are relevant in teaching. How is time experienced, not only in admission processes but also in teaching? What can we gain from using games to think about how time and speed are experienced in education?

Jeuno & Ewa: At KEC, we have a room called the Eggshell-White Room, where we will showcase the concept of ‘the last hour’. We want to thematize time in teaching, and how the person who holds the class needs to think about and structure time more extensively than how time will be experienced by the participants in class. This includes prep time, time for exercises, time for breaks, time for friction, and the flexibility around time such as how long a teacher estimates an activity will take and the rigor of that, as well as break time and frequency. Teachers are conductors of time, responsible for steering it, which can sometimes create anxiety.

This leads to the concept of ‘the last hour’, often happening at the end of a longer teaching session. Time was either compressed, or there wasn’t enough, or just not right: not enough was managed and there is a need to speed up, jump over or fast forward. Or: what happens when the gameplay is over, the materials and scores have been played out, and there is just extra time left in the class? How will this time be used? The last hour is the time most difficult to estimate, as it requires knowledge of the rules and intricacies of the rules according to which one is played by time. In the Eggshell-White Room, this time is presented as unpredictable and potentially anxiety provoking. It’s a space to give meaning to that time by using different concepts of time derived from games. As a project KEC seeks to thematize education from many angles time and speed of teaching/learning is one of them.

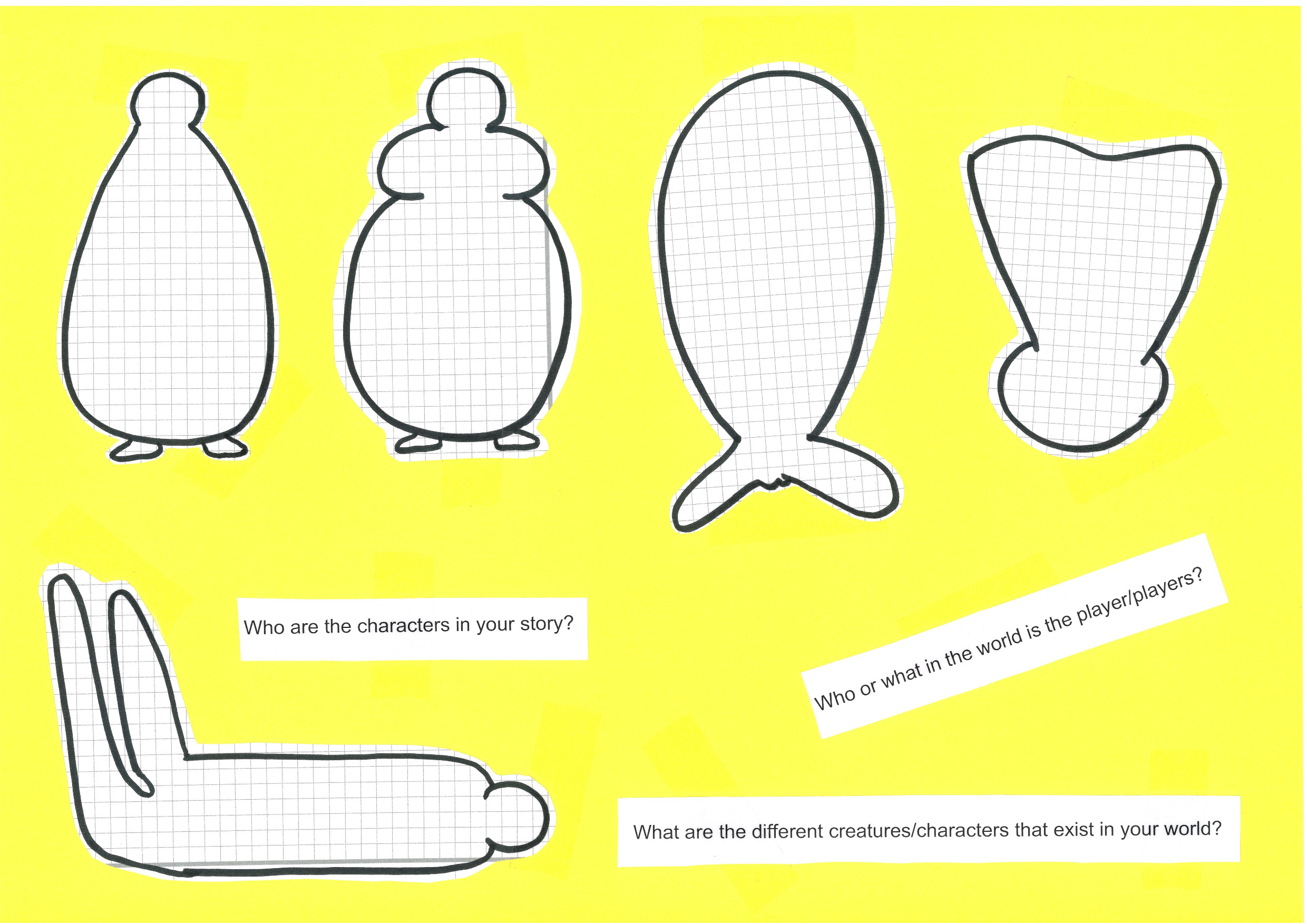

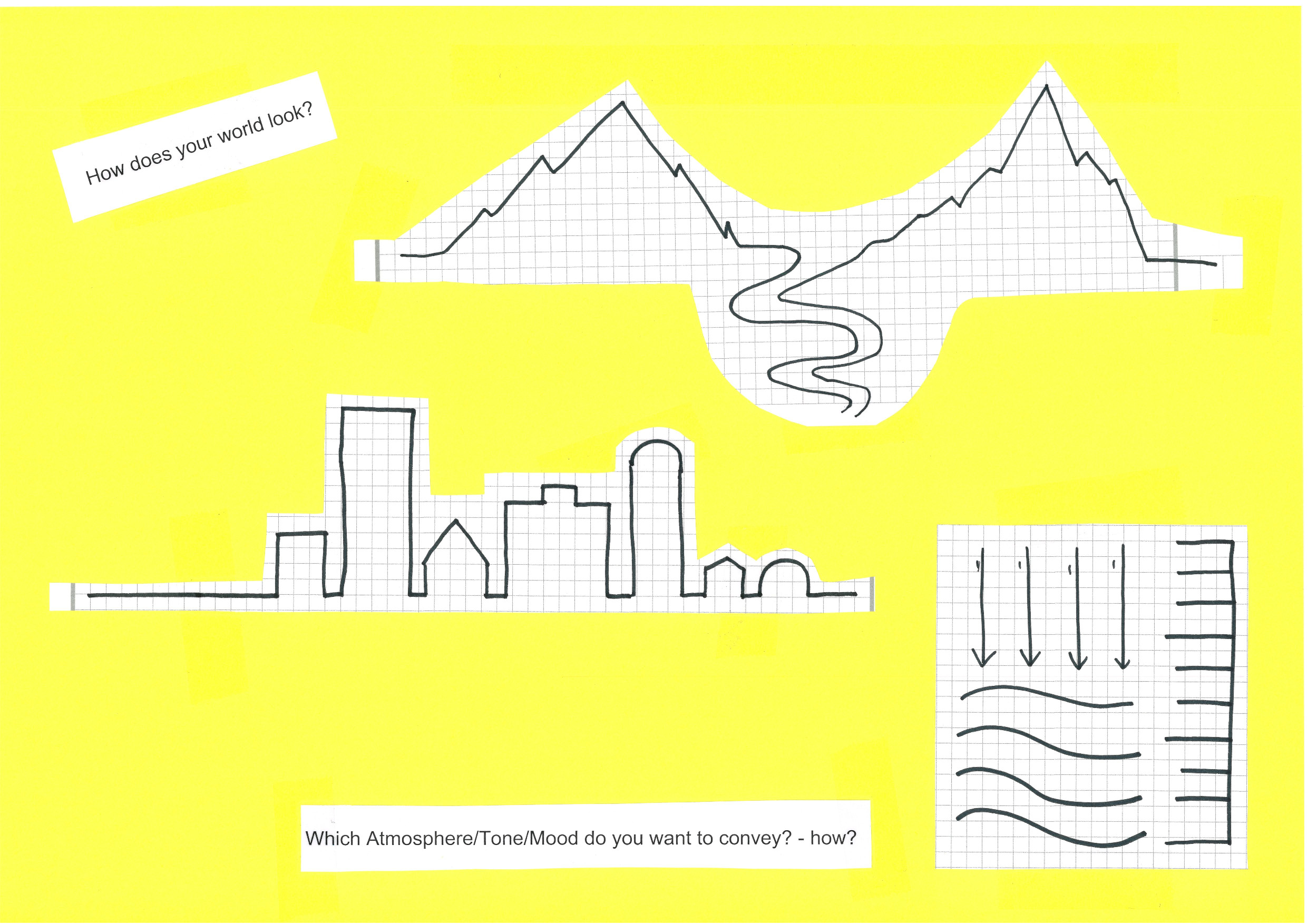

Karolin: When you developed Krabstadt as an animated series, it obviously had a lot to do with world-building: you created a world and populated it with characters, determining how they would move around in that world. This process is similar to how certain game universes are constructed. In the KEC world, for example, there are characters such as students, the dean, admin, maintenance staff, and teachers, as well as buildings and grounds. When describing or drawing them, you get to decide not only what they would look like, but also how they act in order to move the narrative forward. They can function like avatars.

E & J: Yes, at KEC we thought about how the structure of a school entails bodies that have been assigned different roles with consequent responsibilities. These characters are grouped into different organs of the school. To be the dean, the accountant, the jurist, the study leader, the janitor, the teacher, the student can be thought of as different roles played in the game world of education. What is the script in that play of education and how does the script differ from the possible gameplay? What is the performance or the script entailed when we’re supposed to be ‘conducting research’, or delivering a lecture to a group of students, or sitting in a staff meeting deliberating on a student case? Can we play with speaking from different positions in order to better understand and listen to others? Does it make any difference to what we can do if we think of it as a script versus a game?

In Krabstadt there is an abundance of characters with developed backstories. Not all of them are active but they’re still there in the book. Arrabbiata, the Krabstadt volcano, was created in the initial world-building brainstorm, but she wasn’t activated for many years until we decided to make the digital point-and-click game, Arrabbiata Wants a Raise. The game is about a volcano who needs to control her anger in order to get a raise that she hasn’t gotten in several million years. The process of making the game later brought this character into KEC as a teacher, where Arrabbiata is mad from the first day of employment because the school gave her an office that she couldn’t fit into. The admin in charge of onboarding had forgotten to take her size as a volcano into consideration.

World building isn’t just about characters, it’s also about infrastructure, institutions, cartography, architecture, the climate of a place/situation, when we develop KEC as a world within the framework of education we can play with all those elements.

Karolin: Can you say more about working with games in education?

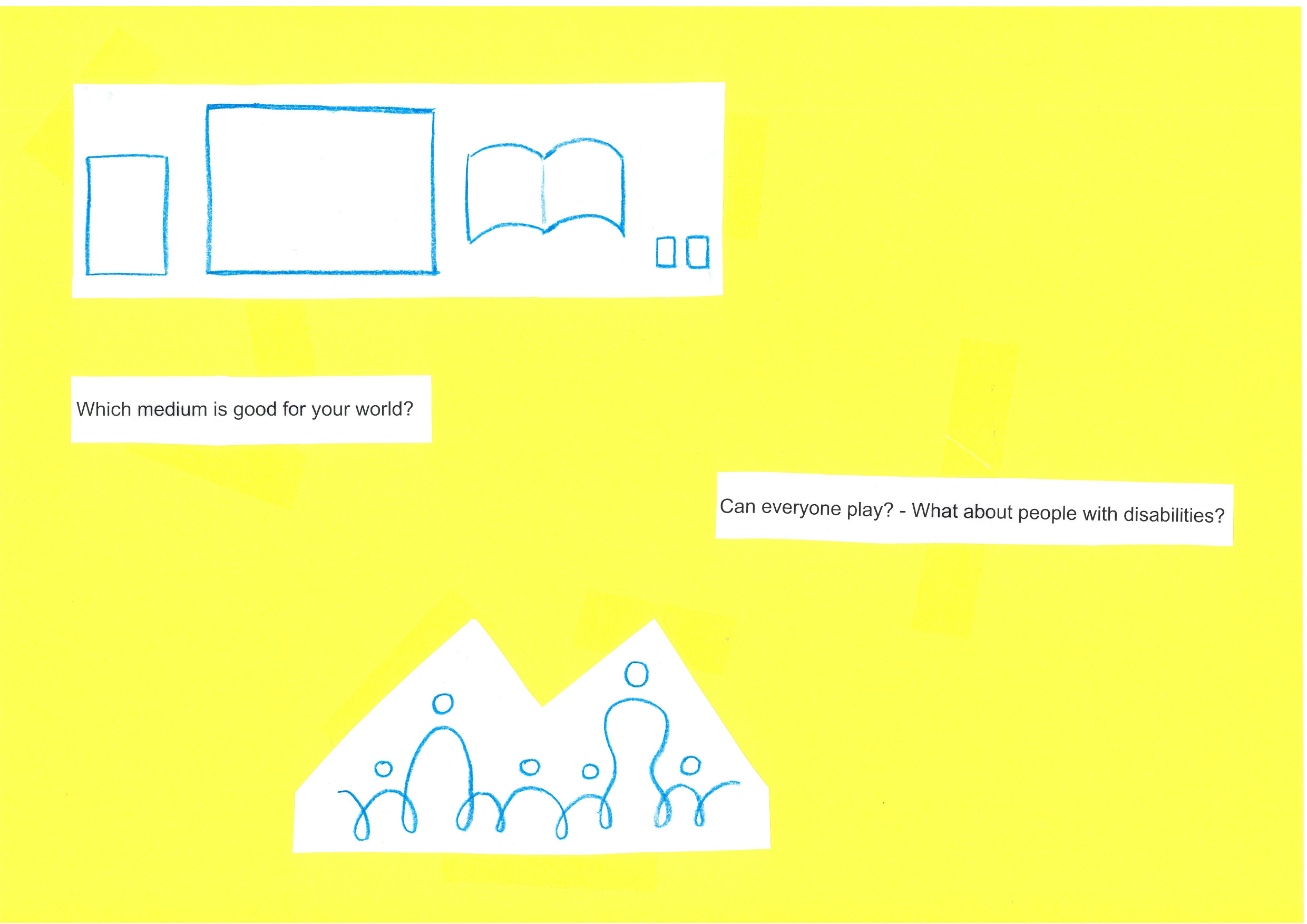

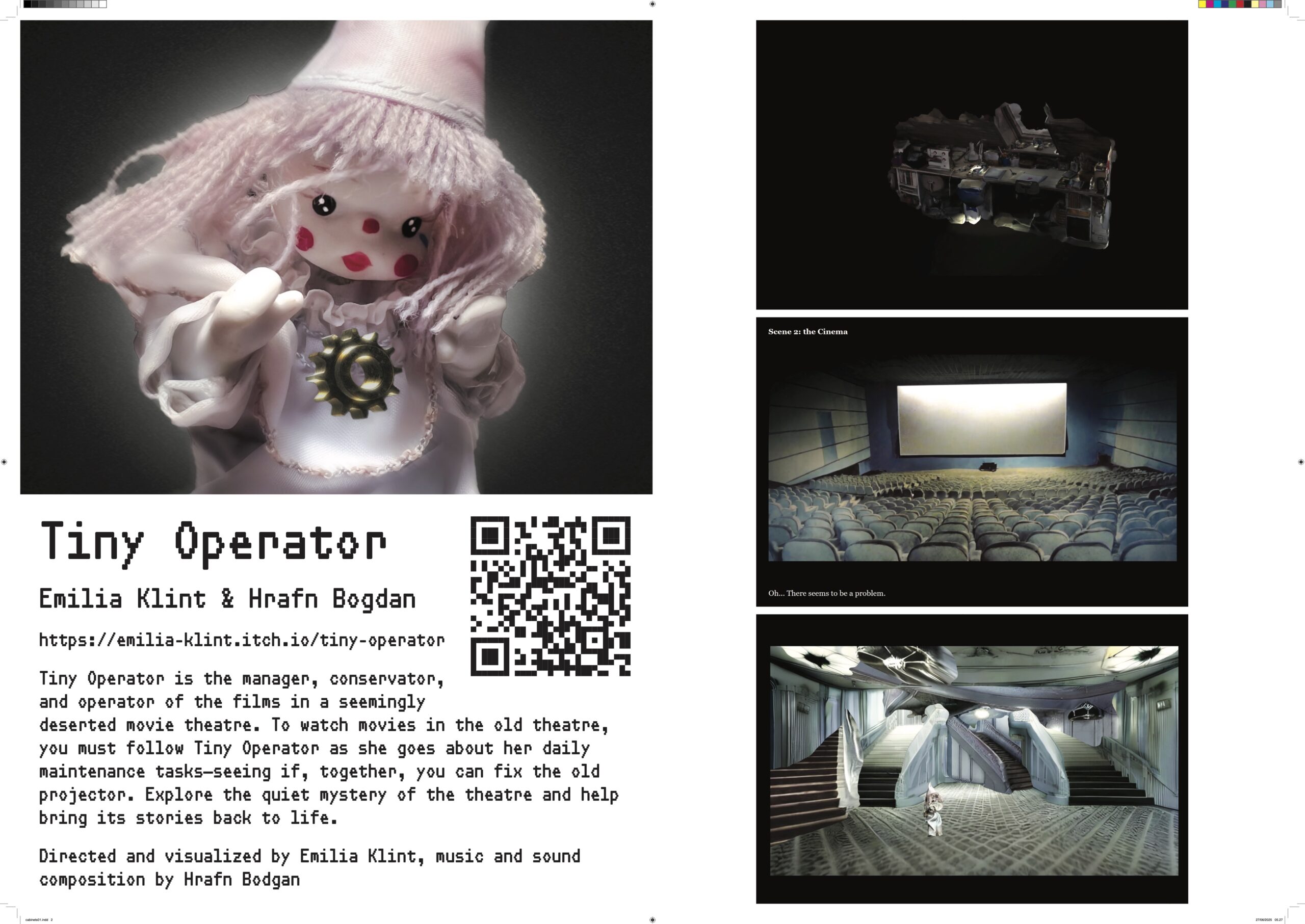

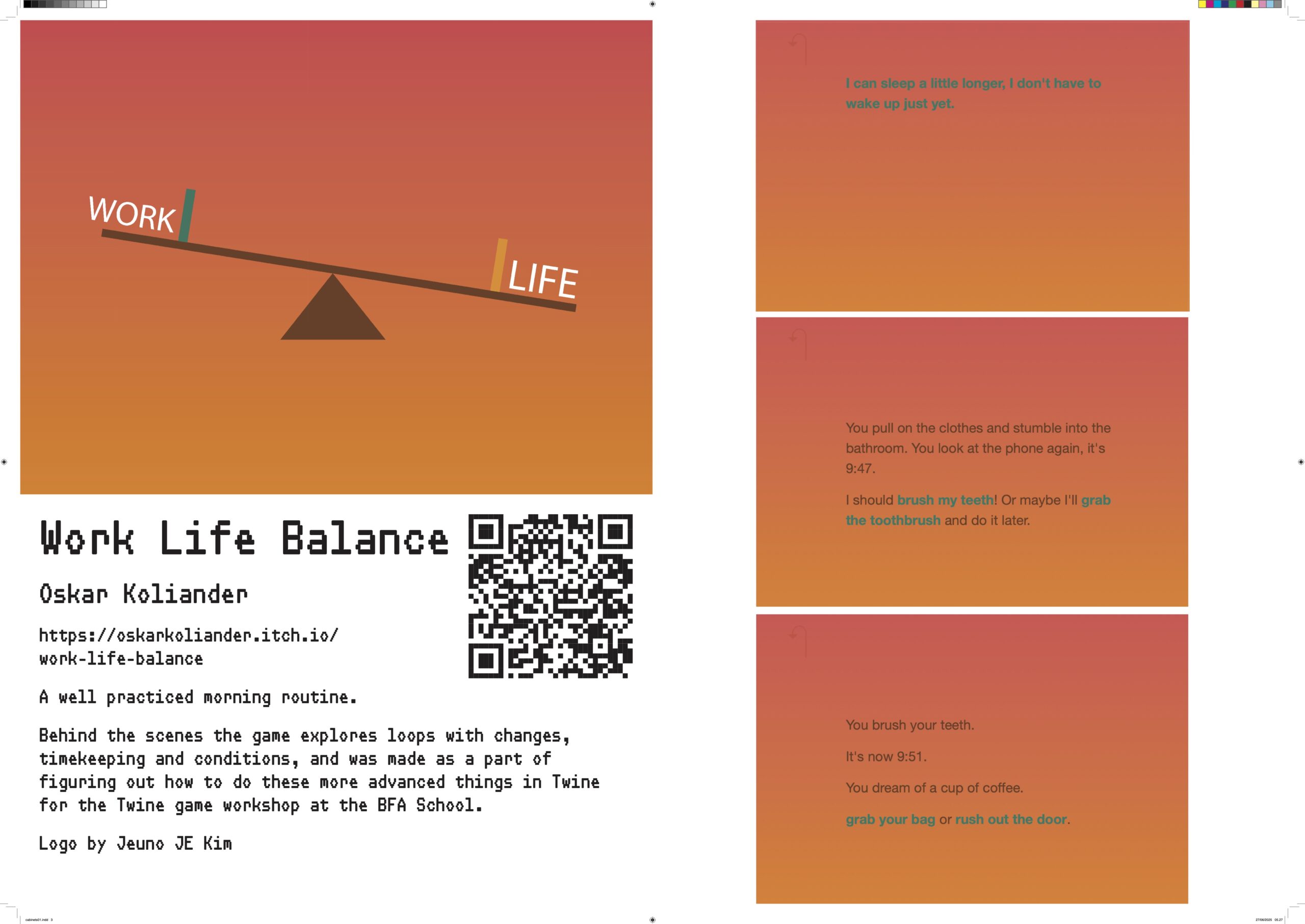

E & J : We have held some lectures and two workshops at the art academy in Copenhagen. The first one focused on making Twine games. Twine is an open source text-based game engine that can be used for telling interactive nonlinear stories. The platform was originally made to create hypertext fiction, but then a bunch of alt-game makers started using it for deeply personal and political games. What is helpful with Twine is that the threshold is very low, allowing for almost anyone to make games. This is part of democratizing the process and accessibility of who gets to make games. For KEC it was a good place to start.

One exercise that we do is about working together as a group and exploring the town. It starts with the group discussing where they are and noticing the different aspects of the place. The final outcome of the discussion is to decide what is the most opposite site to where the group is and that divides the group into two. For example, if the students start at the art academy, they can list out “opposite” places to be a cemetery, a beach, or a sauna. And this would determine how the group would divide and go to the next location. This continues until the students are left as a pair or alone at a site. At each stop they arrive at, they would document the place by noting the physical aspects, how the streets are, listening to the space, seeing how people move etc. We incorporated this physical exercise in the digital game workshop in order to teach students to think about duration and to develop a sense of story or narrative that unfolds over time and in space/location. There is also a kind of mimicking of the Twine structure itself, of nodes splitting, new places or stories being discovered in every location.

Karolin: This splitting into groups is based on different positionalities – it’s like making decisions in games, and your choice determines the path that goes in a different way.

E & J: Exactly. The participants learn to come up with their own questions or problems, which makes them aware of how to make choices and deal with the consequences. From that experience each person or group can then start to develop their own Twine game. You can find the score for the exercise in the Eggshell-White Room under menu item T16.

Karolin: The way you describe the activity, it sounds like a metaphor for the process of making art: you constantly have to make choices. You try to do it in a conceptual way, or you think you are doing it for a certain reason or with a certain intention, but then you end up somewhere else.

E & J: The second workshop we made, ‘Lets Play II’, focused on worldbuilding. We developed another score, T27, which consists of a set of prompts that guided the students to different stages of worldbuilding. The questions are about what rules are in the world, what is the premise, what are the dominant beliefs etc. Each question builds upon the other, but not every question needs to be answered. Sometimes skipping a question is better, but it’s important to read it. We saw students take the questions and either answer them directly to develop and play with them or sip some and use them as negative-question™ or some remained just as unanswered questions.

Karolin: In many education systems where teaching is structured into modules and shorter time units, prompts or assignments are used to organize the teaching. But what does it mean, especially for art students, to get a lot of time-limited, specific inputs with constraints, from which they develop a sketch that they then discuss in class? Is there potential to expand on these scores in their own work? I am thinking, for example, of the work of dancer and choreographer Yvonne Rainer, who often uses scores in her work with dancers to improvise and collect ideas that would later be developed into more complex pieces. For workshop-style teaching, game-based thinking can be very helpful. However, education should also provide the space and time to come to ideas in an unstructured way, the kind of playfulness that emerges from working without a framework. I guess this is KEC’s idea of break-centered learning.

E & J: Exactly. The workshops are kind of compact scenarios where prompts are like catalysts for making/thinking. But then, if you think about education as a whole, its structure is quite gamified because there are levels: you progress from the first year to the second, then the third, and so on. Each class or module has assigned points, and you need to collect them in order to progress. This inculcates in students an obsession or anxiety about points. For example, if you have too many absences, you could fail and not get points, which would set you back in the system. As teachers, we also find ourselves giving students very prescriptive guidelines. For instance, if they’re writing a synopsis, they need to contextualize their works by naming at least two other artists they’re in dialogue with, make a budget, and a production time plan. It sounds formulaic but that is the game we play with the students. KEC flips all of that by engaging with it using game-based thinking.

KEC teaching score classification system:

T – On Site

L – Online

H – Possible for both

B – On a bus or while walking

Numbering

nr 1: everything before KUV

nr:2: invented KUV 1.

nr:3: invented KUV 2

nr: 4: invented Ewa Summer course

Exercises

- KEC-T 1: Cleaving Exercise

- KEC-T 1: Draw a learning space

III. KEC-T 2 : Worldbuilding Questions – Hard and Soft

- KEC-L 4: Parallel Lives Exercise

- KEC-H 4: Hat questions

- KEC-L4: The seesaw game